Module 1: Introduction

“[F]eminists are perhaps alone in the academy in the extent to which they have embraced intersectionality—the relationships among multiple dimensions and modalities of social relations and subject formations—as itself a central category of analysis. One could even say that intersectionality is the most important theoretical contribution that women’s studies, in conjunction with related fields, has made so far. (McCall 2005: 1771, emphasis added)”

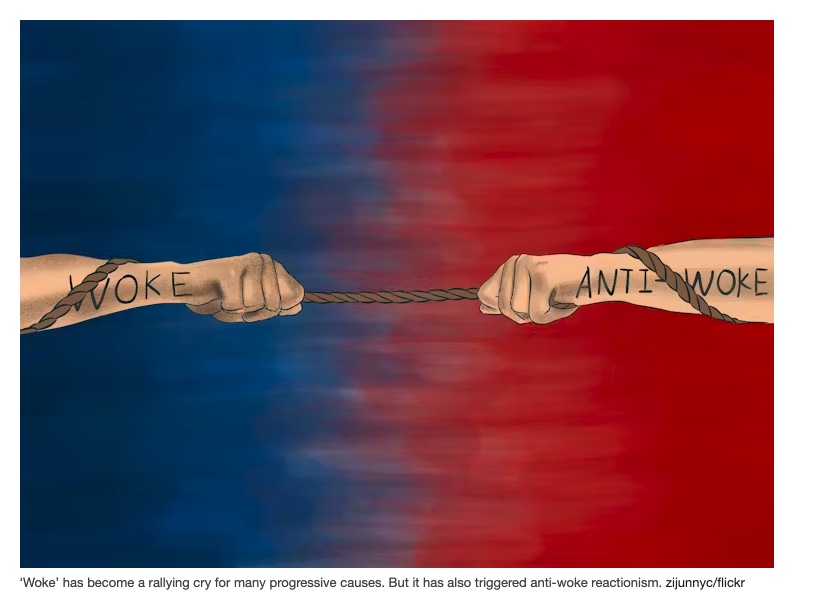

Entering “intersectionality” into any browser search engine will yield around one hundred million results. Indeed, intersectionality seems now everywhere: In his September 2020 throne speech, the liberal then-Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised “a feminist intersectional response to the [COVID] pandemic and recovery,” which, guided by “diverse voices” would help women and especially low-income women, as those hit hardest by the pandemic, back into the workforce. The conservative then-premier of Alberta, Jason Kenney, responded by dismissing intersectionality as “a cooky academic theory.” In the years that followed US, right-wing politicians declared intersectionality “really dangerous” and a “conspiracy theory.” Initially, they introduced bills that sought to ban intersectionality, together with critical race theory, from being taught in high schools and universities. Along with such banning, their aim has been to shut down academic disciplines like Gender Studies, Black and African American Studies that teach these approaches.

Since the inauguration of Donald Trump as the 47th president of the United States in January of 2025, the “war” against intersectionality and everything else perceived as “woke” has rapidly accelerated in the US, but not only there.

At this moment of revising this course, in April 2025, intersectionality, together with anything related to social justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion action and thought has become the target of the Trump administration. All references to intersectionality, diversity, equity and inclusion, and a host of other topics, deemed unacceptable by that administration, such as climate change, vaccines among them, are being scrubbed from government websites and documents. Indeed, PEN America, a non-profit organization dedicated to protecting free speech, compiled a list of more than 250 words and phrases reportedly no longer considered acceptable by the Trump administration.

The attack on social justice research and teaching that we see rapidly unfolding south of the border, however, does not stop there. During the 2025 federal election campaign in Canada, the conservative candidate for Prime Minister, Pierre Poilievre, promised “to target ‘woke ideology’ in university research, describing it as a direct threat to academic freedom” echoing the actions that already have taken place in the US.

The illogicality or hypocrisy of prohibiting and censoring social justice approaches in the name of free speech and academic freedom is hopefully not lost on you as you read this.

On the other hand, in recent decades intersectionality became the lingua franca for social justice-oriented policy initiatives, research, activism, community engagement, and politics. Indeed, intersectionality became so ubiquitous and mainstream that many feared it had lost its radical and transformative edge by becoming simply a “buzzword” (Davis 2008).

In this course, we will address the historical and contemporary debates about intersectionality as theory and praxis. Overall, this course aims to introduce graduate students from across the disciplines and advanced undergraduate students in Women’s and Gender Studies (and related fields) to a deeper understanding of intersectionality as a paradigm for social justice theory, research, and activism. Alongside learning about intersectionality as a methodology, this course will deepen students’ critical research skills.

Learning Objectives

In this module, you will:

● Hone your online learning strategies

● Learn more about intersectionality studies at the University of Alberta

● Consider the contentious ubiquity of intersectionality today

● Learn about methodology – and the difference between paradigm, method, epistemology, and methodology

● Reflect on your own first encounters with intersectionality