SEMINAR (M4)

I am a Mohawk woman. I am a citizen of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy … I am one woman. That’s who I am. I do not represent all First Nations women or even all Mohawk women. My woman identity comes from the fact that I am a member of that Confederacy, that I am a member of the Mohawk nation. You cannot ask me to speak as a woman because I cannot just speak just as a woman… Gender does not transcend race. The voice that I have been given is the voice of a Mohawk woman and if you must speak to me about women, somewhere along the lines you must talk about race. It is out of my race that my identity as a woman develops. I cannot and will not separate the two. They are inseparable. I cannot separate the two because you need to ignore race, because it challenges and confronts your theories and constructions of the world.

This whole idea of double discrimination, that is race and gender, just does not work. … I do not separate that way. My race and my gender are all in one package. My race does not come apart from my woman. That is essentially one of the problems I have with the construction, “violence against women.” It is the initial problem that I have with that concept. I cannot stand up here and just be a woman for you. I cannot stand up here, therefore, and just be a feminist for you. I cannot and will not do it. I do not know how to do it. And it hurts me (and that hurt is violence) that you keep asking me to silence my race under my gender. Silencing me is the hurt which is violence … I cannot trace the discrimination that I live to one source – race or gender. (Patricia Monture-Okanee, 1993, 194- 195)

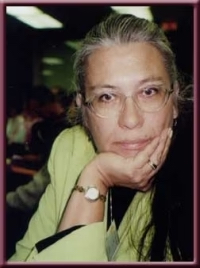

The above excerpt is part of a powerful talk that the late Mohawk legal scholar, activist, and educator Patricia Monture- Okanee gave at a conference on women’s movements in Canada and the US, at the University of Western Ontario, London, in May of 1989. Published a few years later in 1993, under the provocative title “The Violence We Women Do: A First Nations View,” Monture-Okanee’s talk arguably embodies an intersectional sensibility – before the term intersectionality was coined.

REFLECT:

Take a moment to identify different aspects in this text passage that represent an intersectional-type approach.

In my own teaching, I have drawn on Patricia Monture-Okanee’s text for over two decades to show how intersectionality is not the exclusive intellectual property of Black US feminism.

In her talk, Montue-Okanee:

- Challenges a single-axis feminist analysis of violence against women that is exclusively gender-based;

- refuses to separate her identity as a woman from being Mohawk;

- underlines the (intracategorical) diversity among different Indigenous tribes and among Mohawk women;

- rejects the notion of an additive model or “double discrimination.”

In the remainder of her talk, she challenges white feminists to expand their understanding of consent, violence, and power. Within the context of settler colonialism, she argues that educational institutions, legal systems, and Western definitions of knowledge were all imposed on Indigenous peoples without consent and against their will. She terms “the violence we women do” as the failure to recognize this colonial imposition as a form of violence—one that has ongoing consequences for Indigenous peoples and contributes specifically to violence against Indigenous women.

Monture-Okanee critiques the feminist violence against women discourse at the time, for failing to attend to the constitutive role of settler colonialism in Indigenous women’s experiences of violence. She does not merely assert an intersectional identity for Indigenous women, although she does that too. Rather, she provides an analysis akin to what Crenshaw in 1991 termed “structural intersectionality,” demonstrating how violence against Indigenous women is rooted in their disempowerment due to the imposition of the structure of settler colonialism on Indigenous peoples.

Red Intersectionality

As already mentioned, there is no agreement among feminist Indigenous scholars, creators and activists in regards to intersectionality, its utility for and relationship to Indigenous theorizing. Some Indigenous scholars and activists see nothing new in intersectionality, while others develop a specific Indigenous or “Red” intersectionality, which transcends, like Monture Okanee earlier, an understanding of “complex identities”. Red intersectionality as defined, for example by Natalie Clark (2016), a Professor of Social Work at Thompson River University of mixed Settler, Secwepemc and Metis heritage, involves different ways of knowledge production: “Indigenous intersectionality as a theory invites and even calls for a new way of writing that has been ignored largely in current intersectional scholarship” (Clark, 2016, 48).

Red intersectionality, so Clark, is not or not just grounded in an analysis of the long history of of multi-vector victimization of Indigenous women and girls, but in rejecting a victim-focussed approach. For Clark, red intersectionality centers the long history of Indigenous women and girls as organizers, freedom fighters, and healers (Brant cited in Clark 2016, 49).

Red intersectionality considers Indigenous and tribal specific ontologies and epistemologies, which long have been marginalized, denied and violently repressed in settler colonial societies. For Clark’s work with Indigenous girls, this means recognizing

the importance of local and traditional tribal/nation teachings, and the inter-generational connection between the past and the present, while also recognizing the emergent diversity of Indigenous girlhood and the geographic movement off and on reserve, and the construction of Indigenous girls through the Indian Act. A Red intersectional perspective of Indigenous girls and violence does not center the colonizer, nor replicate the erasure of Two-Spirit and trans peoples in our communities, but, instead, as I have already mentioned, attends to the many intersecting factors including gender, sexuality, and a commitment to activism and Indigenous sovereignty. (Clark, 2016, p. 51)

A red intersectionality framework, according to Clark, is “inherently activist, responsive to local and global colonization forces, and theorized for the emergent … indigenous [sic] identity with the clear goal of sovereignty .. [and] to serve and inform Indigenous struggle for selfdetermination” (Clark, 2016, 50).

Indigenous Dialogue on Intersectionality

To address the already noted relative absence of Indigenous voices in intersectional scholarship, the Institute for Intersectionality Research and Policy at Simon Fraser University, organized by Sarah Hunt (member of the Kwagiulth, Kwakwaka’wakw Nation), then a PhD candidate, hosted in 2012 a community dialogue on Intersectionality and Indigeneity in Coast Salish Territories (downtown Vancouver). Hunt’s report, which is part of the assigned readings for this module, offers a snapshot of the diverse views on intersectionality offered by the group of Indigenous people gathered that day. Participants with diverse backgrounds in academia, human services, community activism, and the arts shared both professional knowledge, personal experiences, and community histories relating to intersectionality.

This exploratory dialogue was organized around a set of questions, also relevant to this module:

- Is intersectionality, as it is currently understood, truly a good fit for understanding Indigenous lives and worldviews under neo-colonialism?

- How do Indigenous understandings of colonization, and its hegemonic ideologies and practices, mesh with intersectional theory?

- How can the enactment and resurgence of Indigenous laws, cultural practices and worldviews find a central place in intersectional frameworks?

- How can colonial oppression be voiced along with the agency of Indigenous peoples and the active nature of their/our ongoing cultural, spiritual, political and legal practices?

- What approaches are being used in Indigenous communities and by Indigenous scholars that share similarities with intersectionality without using the language of intersectionality?

- How might we begin to talk about indigenous intersectional frameworks? Is this appropriate or desirable?