SEMINAR (M5)

The unit presents South Asia as a case study. More specifically it considers debates among feminists in India who have questioned whether intersectionality can be used as a theory and methodology to explore the conditions of oppression in the particular contexts of casteism, religiosity, ethnic diversity, postcoloniality in a neoliberal setting.

Nivedita Menon, one of the scholars whose work we explore in this chapter, raises the point that the Global South has time and again been used as a laboratory for legitimizing presumptions by academics based outside the region. This concern is valid. Much research has selectively chosen, and sometimes distorted, versions of cultural practices, social behaviour and other aspects of identity for racialized people and communities in the Global South to feed Western preconceived notions of these groups and individuals. Historically, such studies have used racially biased Eurocentric lenses to construct non-European cultures, societies, and peoples as imperfect renditions of humanity. These logics were used to justify both human rights violations and “saviorism” by European forces during the colonial era.

So, essentially, Menon and others who question the applicability of intersectionality in the Global South are framing the use of intersectionality in a global-historical context of Western academic supremacy. They suggest that instead of exporting and imposing theories from the Global North onto the Global South, Western academics should read and understand theories that emerged out of the Global South as these theories are based on the conditions of these regions. For example, Nigerian scholar Oyeronke Oyewumi points out that Western anthropologists while studying African societies apply theory based on their own presumptions while ignoring the phenomenon on the ground: “If the investigator assumes gender, then gender categories will be found whether they exist or not” (quoted in Menon, p. 37). Thus, the issue of universality of theory in general, and more specifically that of intersectionality and its applicability in the Global South, is concerned with the wider question of research ethics.

Postcolonial critic and theorist Edward Said argued that theory is “a response to a specific social and historical situation of which an intellectual occasion is a part” (1983, p. 237). As such if devoid of its particular contextualization, theory loses its radicality. (Though Said also entertained the possibility of travelling theory holding a more transgressive promise.)

Imposing Western Concepts?

In this module, we continue discussing what we earlier distinguished as political intersectionality. Critics we have read earlier (like Carastathis, 2016) point to the risks of mainstreaming intersectionality. In the context of this module, we consider the risks of globalizing intersectionality and the categories of differences intersectionality attends to. The concern is with intersectionality becoming a simplistic tool of neoliberal standardization of development and equality measures.

Commenting on intersectionality’s spatial trajectory, Manjari Sahay (2019) writes in “The Travel/Trial of Intersectionality” :

“When the context is one of unequal power relations between countries, including unequal epistemic authority, the travel of theory cannot be treated as apolitical movement or even happenstance, independent of colonialism and imperialism. Attached to this are epistemic consequences, which are also political ones.”

This quotation invites a re-evaluation of the positionality and power difference between Western theories and researcher and the subjects of their research.

We know that academics located in the Global North often bring their toolbox, which includes intersectionality, to “study” problems of the Global South. This process prevents the possibility of looking for and fostering organic development of theory grounded in the social conditions in the Global South. Moreover, lesser-known theories and theorists that emerge to explain particular or specific conditions related to the Global South are often ignored or sidestepped to make room for more well-known theories, concepts, and methodologies. (This is reminiscent of the ethics of citation addressed earlier in the course.)

Consequently, academic scholarship on multiple and intersecting oppressions emerging from South Asia, Africa, and Latin America are marginalized and missing from much of academic discussions on intersectionality.

This Module asks us to question the politics and ethics involved in imposing Western research tools to analyze the Global South. We need to acknowledge the hegemonic influence of the US academy and evaluate how “intersectionality” as a US-born concept carries this hegemonic force when imported to the Global South.

The articles we study in this Module address this as an ethical issue. They ask us to consider how the use of US-born theories and methodologies to “read” contexts of the Global South risks substantiating (rather than challenging) the power and legitimacy of the US academy. Further, we need to question whether this process of imposing Western concepts, theories, and tools, distorts or limits the phenomenon or social context under review.

The critical questions we are asked to consider then are as follows:

- What are the risks and benefits of imposing Western categories of social difference, such as gender, sexuality, ethnicity, race, etc. onto contexts of the Global South?

- Does the export of the critical paradigm of intersectionality, despite its progressive and liberatory intentions, risk furthering the dominance of the West over the Global South?

- Is Intersectionality a universal theory/or research method that can explain the structure of oppression faced by marginalized groups irrespective of space and time?

- What do we lose when intersectionality travels to postcolonial societies (like India)?

Background: Global South

According to Anne Garland Mahler’s “What/where is the Global South” as a critical concept “Global South” encompasses three different primary definitions:

What/Where is the Global South?

By Anne Garland Mahler, University of Virginia

The Global South as a critical concept has three primary definitions.

First, it has traditionally been used within intergovernmental development organizations –– primarily those that originated in the Non-Aligned Movement –– to refer to economically disadvantaged nation-states and as a post-cold war alternative to “Third World.” However, in recent years and within a variety of fields, the Global South is employed in a post-national sense to address spaces and peoples negatively impacted by contemporary capitalist globalization.

In this second definition, the Global South captures a deterritorialized geography of capitalism’s externalities and means to account for subjugated peoples within the borders of wealthier countries, such that there are economic Souths in the geographic North and Norths in the geographic South. While this usage relies on a longer tradition of analysis of the North’s geographic Souths –– wherein the South represents an internal periphery and subaltern relational position –– the epithet “global” is used to unhinge the South from a one-to-one relation to geography.

It is through this deterritorial conceptualization that a third meaning is attributed to the Global South in which it refers to the resistant imaginary of a transnational political subject that results from a shared experience of subjugation under contemporary global capitalism. This subject is forged when the world’s “Souths” recognize one another and view their conditions as shared (López 2007; Prashad 2012). The use of the Global South to refer to a political subjectivity draws from the rhetoric of the so-called Third World Project, or the non-aligned and radical internationalist discourses of the cold war.

In this sense, the Global South may productively be considered a direct response to the category of postcoloniality in that it captures both a political collectivity and ideological formulation that arises from lateral solidarities among the world’s multiple Souths and moves beyond the analysis of the operation of power through colonial difference towards networked theories of power within contemporary global capitalism.

Critical scholarship that falls under the rubric of Global South Studies is invested in the analysis of the formation of a Global South subjectivity, the study of power and racialization within global capitalism in ways that transcend the nation-state as the unit of comparative analysis, and in tracing both contemporary South-South relations –– or relations among subaltern groups across national, linguistic, racial, and ethnic lines –– as well as the histories of those relations in prior forms of South-South exchange.

REFLECT:

Paraphrase the three different meanings of Global South:

1.

2.

3.

Context: Dalit Movement and Dalit Feminism

Before you read the assigned article for this Module, you will need to understand the concepts of Dalit feminism, caste hierarchy, and oppression in Hindu society.

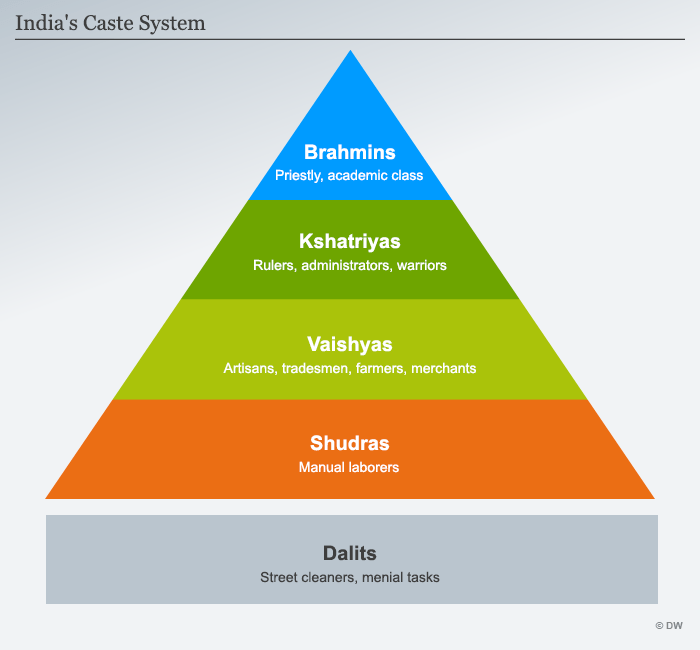

There are four castes in a traditional Hindu society: All other people fall outside of the caste system and are outcastes – who are also called Dalits.

The Indian state is a secular entity and caste-based discrimination in any aspect of life is legally punishable by the state. However, the long cultural tradition of discrimination has maintained the marginalization of Dalit communities from full social participation.

The Dalit movement addresses caste-based discrimination and oppression and fights for equal rights and treatments in every aspect of life.

Dalit feminism emerged as a separate branch of feminism. Most feminist activism and scholarship in India is dominated by upper-caste women (both liberal and Marxist), also called Savarna feminist movements.

The broader Dalit movement does not center the issues of gender-based oppression that define the lived experiences of Dalit women.

The Dalit feminist movement aims to challenge the position of victimization that has been assigned to Dalit women by both the Dalit movement (which frames the women as powerless victims of caste oppression) and by the Savarna (non-Dalit) feminist movement. The Dalit feminist movement asserts Dalit women as agents of change and demands that the state offer them full rights of citizenship.

An example of the conflict between Savarna and Dalit feminists is the debate that erupted when the Indian government introduced a ban on bar dancing. The Marxist-socialist (non-Dalit) feminists of the country protested this ban as it threatened the livelihoods of workers who earn a living through this occupation. However, many Dalit feminists supported this ban as they pointed out performing for the sexual pleasure of heterosexual men outside a marriage was not only sexist but also “casteist.” Dalit women come from castes that traditionally have been forced into sexwork related professions. Thus, Dalit feminists argued that the ban protects Dalit women from both caste-specific sexual exploitation by upper-caste men and patriarchal society.

Background: Governmentality

The main reading in this module, by Nivedita Menon provides a critical view of exporting intersectionality to the Indian context. In order to understand Menon’s argument about how intersectionality has been coopted, you need to familiarize yourself with the concept of governmentality:

The concept of governmentality was introduced in the later work of Michel Foucault as a more refined way of understanding his earlier idea of power/knowledge. Government refers to a complex set of processes through which human behaviour is systematically controlled in ever wider areas of social and personal life.

For Foucault, such government is not limited to the body of state ministers, or even to the state, but permeates the whole of a society and operates through dispersed mechanisms of power. It comprises both sovereign powers of command, of the kind that figure in traditional political science and political sociology, and disciplinary powers of training and self-control.

Sovereign power is coercive and repressive, involving exclusion through external controls and inducements.

Disciplinary power, on the other hand, concerns the formation of motives, desires, and character in individuals through techniques of the self. Disciplined individuals have acquired the habits, capacities, and skills that allow them to act in socially appropriate ways without the need for any exercise of external, coercive power.

Disciplinary power developed in the modern period through such means as schools, hospitals, military barracks, and prisons, and a particularly important focus is the family itself. It is through the disciplinary agency of the family that selves and bodies are regulated at the most intimate level. Foucault traces the emergence of a whole array of ‘experts’, based in scientific ‘disciplines’ and involved in the disciplining of individuals. It is through all these means that governmentality takes place.

“governmentality.” Oxford Reference. ; Accessed 25 May. 2024. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095901877.

REFLECT:

What is the difference between “sovereign” and “disciplinary” power? How do they work together in governmentality?