SEMINAR (M6)

What is Policy?

Any organization that you are part of, whether that is a sports club, a political party, a student group, a church or religious institution, the university, your work place, etc. will be governed by policies.

Policy refers to a set of principles, rules, or guidelines formulated or adopted by an organization, government, or institution to achieve specific long-term goals. Policies provide a framework for decision-making and actions, aim to guide behavior and ensure consistency in addressing particular issues or situations. They can be implemented at various levels, including local, national, and international, and across various domains such as health, education, environment, and economy.

Key aspects of policy include:

- Objective: The specific aim or goal that the policy is designed to achieve.

- Guidelines: The principles or rules that dictate how the policy should be implemented and adhered to.

- Implementation: The process of putting the policy into action, often involving various stakeholders.

- Evaluation: Assessing the effectiveness of the policy in achieving its objectives and making necessary adjustments.

Policies can be formal, written documents, or informal, unwritten practices that have become standardized over time.

Policy often seem benign and purely “bureaucratic” or are experienced as authoritative documents that cannot be questioned. However, policies are written by people, people who bring their own preconceived notions, beliefs, habits, personal, organizational, or institutional traditions to the process. Thus policies often are shaped by, and in turn, shape and maintain unequal power dynamics. Often the people who are most affected by policies are not the ones writing them. Since policies govern many if not all aspects of an organization, they are documents with powerful effects.

What does Policy do?

Throughout this course, we have encountered examples of policies perpetuating injustice and oppression because of their single vector approach. For instance, Hancock (2007) critiques welfare reforms concerned only with gender inequality at the expense of other categories of social difference. Her examples include polices aimed at supporting single mothers after divorce by enforcing legally assigned child support payments. Hancock demonstrates how these well-intended gender-based policies only benefit heterosexual, middle-class women whose former partners have garnish-able incomes. They do little to support the former spouses of poor or unemployed men, lesbians and other single parents without “legally obliged” former partners (252). Or, remember, Crenshaw’s (1991) critique of language requirements for admission to women’s shelters and the potentially deadly effects these can have on immigrant women with limited English language skills fleeing domestic violence.

These are but two examples of how equity and social justice initiatives, however well intended, might have the opposite effect when complex casualties are ignored and when only one social category (only ‘race’, only gender, only sexuality, only Indigeneity etc.) is considered in understanding people’s needs and experiences.

Against Oppression Olympics

That said, it is important to remember that intersectionality does not promote an “add-on” approach either, where the impact of racism, sexism, ageism, heteronormativity, classism, ableism and other forms of oppression are simply ‘stacked’ on top of each other in an additive model of “multiple” or “double oppressions”. Intersectionality is not an “oppression Olympics.”

WATCH:

The complex challenge of an intersectional approach involves analysing and attending to the complex ways that social categories are interacting with and co-constituting one another to create unique social locations that vary according to time and place (Hankivsky & Cormier, 2009). This also means that some categories matter sometimes and in some contexts but not in others.

Identities vs. Social Location

I think by now we all understand that an intersectional paradigm begins from the understanding that inequities can not, or only rarely, be explained through a single vector of power – it’s racism! It’s sexism! It’s ableism and so on. Instead, inequities overwhelmingly are the “outcome of intersections of different social locations, power relations and experiences” (Hankivsky 2022, 2):

Intersectionality promotes an understanding of human beings as shaped by the interaction of different social locations (e.g., ‘race’/ethnicity, Indigeneity, gender, class, sexuality, geography, age, disability/ability, migration status, religion). These interactions occur within a context of connected systems and structures of power (e.g., laws, policies, state governments and other political and economic unions, religious institutions, media). Through such processes, interdependent forms of privilege and oppression shaped by colonialism, imperialism, racism, homophobia, ableism and patriarchy are created. (Hankivsky, 2022, 2)

It’s worth pausing to read the above quotation slowly, maybe even aloud, to take note of the language Hankivsky uses.

Hankivsky speaks of “social locations” rather than identities; and of “interactions,” rather than intersections. What difference does it make to your understanding to think of ‘race’/ethnicity, Indigeneity, gender, class, sexuality, geography, age, disability/ability, migration status, religion etc. as “social locations’ rather than identities?

Understanding these categories as social locations shifts the focus from personal, individual characteristics to broader societal contexts and structures. It highlights power dynamics, systemic, and institutional factors that categorize, locate, and govern people, such as laws, policies, the state, religious institutions, media, health care, etc.

By comparison, thinking of race/ethnicity, Indigeneity, gender, class, sexuality, geography, age, disability/ability, migration status, and religion as identities emphasizes individual experiences, self-concepts and how people understand and express themselves.

In her definition of intersectionality, Hankivsky focuses on a structural analysis, that emphasizes that social locations intersect within larger power structures, leading to intertwined forms of privilege and oppression. This perspective is essential for addressing social inequalities and promoting social justice.

Key Tenets of Intersectionality

Key Tenets of Intersectionality (Hankivsky 2022, 3)

• Human lives cannot be explained by taking into account single categories, such as gender, race, and socio-economic status. People’s lives are multi-dimensional and complex. Lived realities are shaped by different factors and social dynamics operating together.

• When analyzing social problems, the importance of any category or structure cannot be predetermined; the categories and their importance must be discovered in the process of investigation.

• Relationships and power dynamics between social locations and processes (e.g., racism, classism, heterosexism, ableism, ageism, sexism) are linked. They can also change over time and be different depending on geographic settings.

• People can experience privilege and oppression simultaneously. This depends on what situation or specific context they are in.

• Multi-level analyses that link individual experiences to broader structures and systems are crucial for revealing how power relations are shaped and experienced.

• Scholars, researchers, policymakers, and activists must consider their own social position, role and power when taking an intersectional approach. This “reflexivity,” should be in place before setting priorities and directions in research, policy work and activism.

• Intersectionality is explicitly oriented towards transformation, building coalitions among different groups, and working towards social justice.

REFLECT:

If you are working on a project or paper in this course, pause and consider each tenet and how it might be relevant to your project or paper:

- How does your work seek to contribute to social justice?

- Which categories and interacting social locations matter to your work? How have you come to this conclusion?

- Which power dynamics does your work consider?

- What role do complex and shifting relations of privilege and oppression play and how do you attend to that in your work?

- What links do you note and attend to in your work between experiences and power relations?

- What is your positionality, role and power, in relation to your knowledge-creation work?

Intersectionality-Based Policy Framework (IBPA)

Hankivsky, Olena. 2022. “Intersectionality 101.”https://resources.equityinitiative.org/handle/ei/433.

Hankivsky et al. (2012) developed a framework for intersectionality-based policy to guide through intersectional policy analysis, though it is also useful for research, teaching, and other forms of knowledge creation.

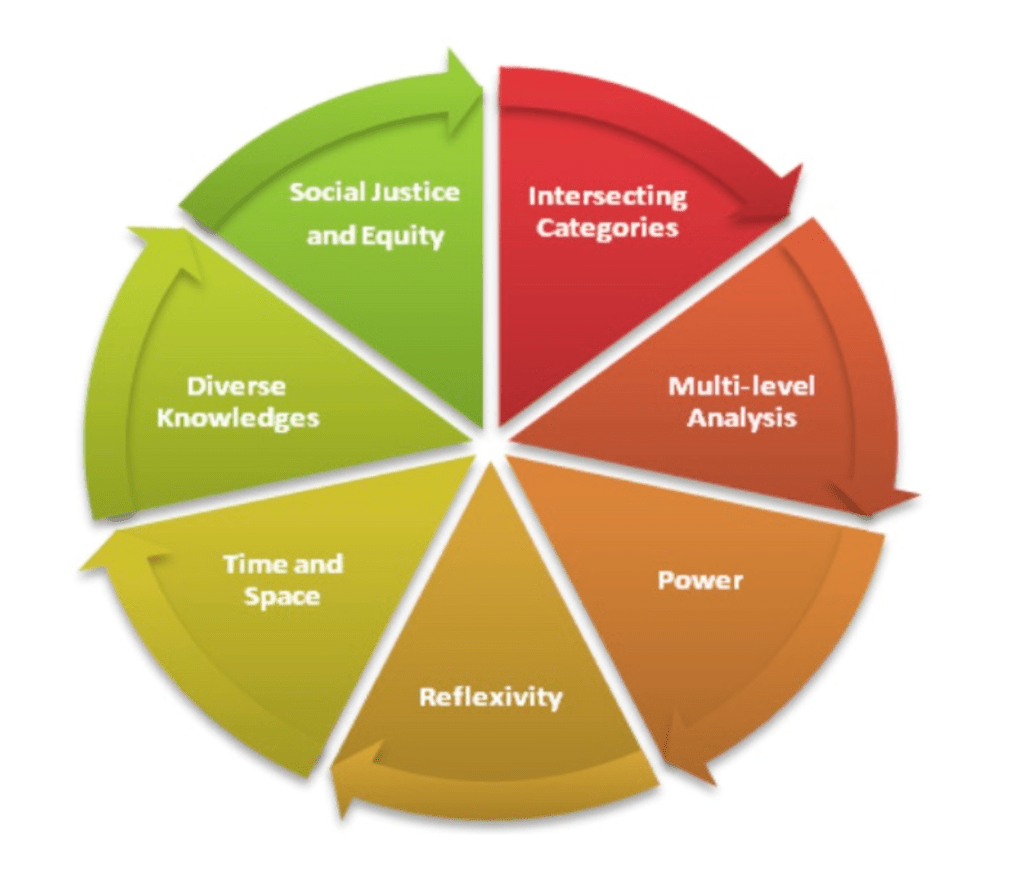

The Intersectionality-based Policy Analysis Framework (IBPA) involves seven aspects:

- Multi-level analysis

Intersectionality examines the interactions and effects of various social levels—macro (global/national), meso (regional), and micro (community/individual)—on structures, identities, and representations, emphasizing that these relationships and their significance are uncovered through intersectional research and analysis. This multi-level approach highlights the necessity of addressing inequities and differentiation across these levels.

- Power

Intersectionality views power as operating discursively and structurally to shape knowledge, experiences, and subject positions, influencing shifting forms of privilege and oppression across and within groups. Power is relational (power over/power with and to) and shifting. It rejects competing for the “most oppressed” status, focusing instead on the intersecting processes that produce, reproduce, and resist power and inequity.

3. (Self)Reflexivity

Intersectionality incorporates reflexivity to address power at both individual and societal levels, recognizing multiple truths and prioritizing voices typically excluded from policy roles. Reflexive practices involve researchers’ ongoing dialogue about various forms of knowledge and their influence on policy, encouraging critical self-awareness and questioning of assumptions to transform policy, including reconsideration of connections to colonization.

4. Time and Space

Shifting dimensions of time and space matter to intersectional analyses as experience, knowledge, social order, and understandings of the world are time and space specific. This also means that oppressions and privileges change within different dimension of time and space as do interpretations and feelings.

5. Diverse Knowledges

Intersectionality examines the link between power and knowledge production, emphasizing the importance of including marginalized perspectives to disrupt dominant power structures. By incorporating diverse knowledges, such as Indigenous traditions, intersectionality-based policy analysis (IBPA) challenges conventional notions of “evidence” and addresses inequities in policy making.

6. Social Justice

Intersectionality emphasizes social justice, focusing on redistributing goods or transforming social processes to achieve equity. This approach challenges inequities at their source and promotes new ways of thinking and living that enable dignified, ecologically sustainable lives, thereby addressing the root causes of inequities.

7. Equity

Equity, closely linked to social justice, concerns fairness in designing social systems to equalize outcomes between advantaged and disadvantaged groups. Unlike equality, which measures differences, equity addresses unfair or unjust differences, and the IBPA Framework extends traditional gender equity analysis to include multiple intersecting positions of privilege and oppression.

8. Resistance and Resilience

Resistance and resilience, though not formal principles of IBPA, are crucial for disrupting power and oppression from marginalized positions. These concepts challenge dominant ideologies through collective actions and highlight that labeling groups as inherently marginalized undermines the potential for coalition-building by obscuring shared power relationships.

REFLECT:

Consider each of the seven aspects of the IBPA in relationship to your own work:

- Which aspects are especially salient for your work and why?

- Which aspects does your work already address and how?

- Which aspects do you need to develop further?

- Which ones do you deem irrelevant and why?

Questions for Policy Makers and Policy Analysis

While intersectional policy making and intersectional policy analysis are still very much in development, in recent years, several organizations have developed tools and toolkits to help critically analyze policy and, to support individuals and organizations developing policy using an intersectional lens.

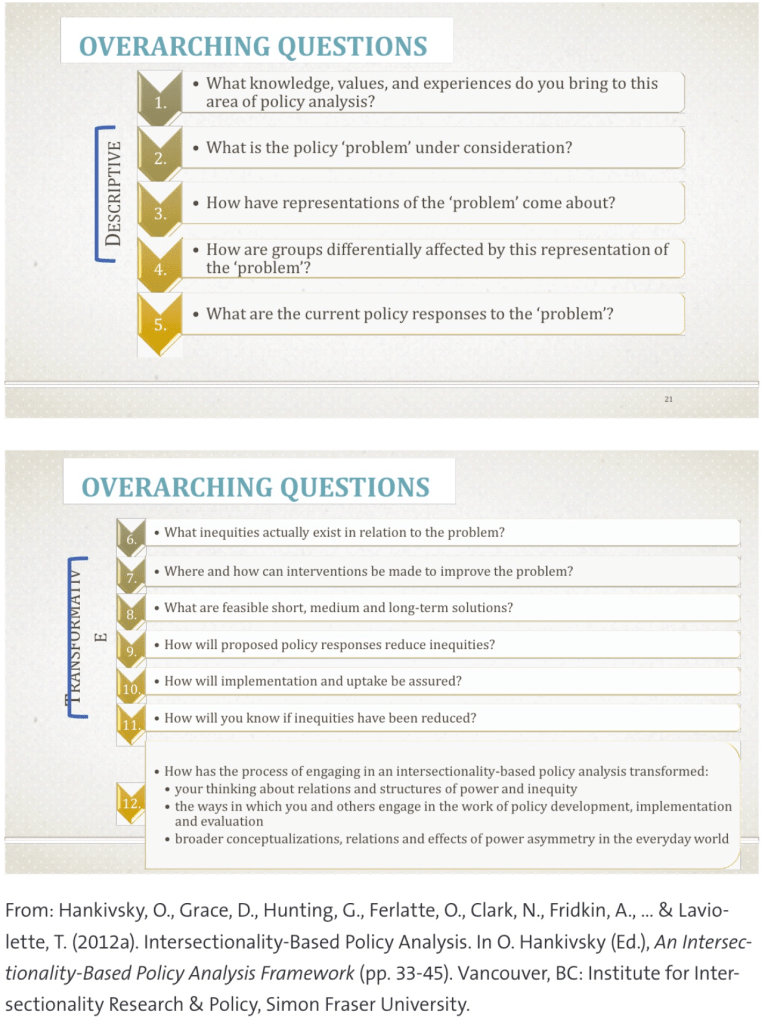

Hankivisky et al (2012a) suggest the following overarching reflexive and analytical questions for critical evaluation of existing or new policies. The questions are organized into “descriptive” and “transformative” questions.

REFLECT:

Reading these questions, how would you describe the difference between descriptive and transformative questions?

Policy Analysis Tool

Based on the IBPA tool developed by Olena Hankivsky et al, the “Make Way” Programme as part of its commitment to increasing sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) through the use of an intersectional lens, has developed an extensive intersectional policy analysis tool. (“Make Way” is funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands and has many partner organizations in Africa.)

The tool offers a structured approach for conducting policy analysis. It helps identify key stakeholders and relevant policies for further examination, pinpoint potential alliances, and assess opportunities and challenges. Utilizing this tool allows posing critical questions about a policy, uncovering its proponents, and considering aspects that might be overlooked in a typical policy analysis process. It incorporates an intersectional perspective, enabling a deeper understanding of the power dynamics embedded in policies. By humanizing the policy process and considering the individuals impacted, the tool encourages a shift towards a framework that prioritizes the goal of “leaving no one behind” in every policy decision.

The tool consists of 36 questions that help policymakers, advocates, and other stakeholders to use an intersectional lens for analyzing any policy by reflecting on:

- the policy’s ecosystem

- the perspectives that underpin the policy

- the policy development process

- the people or identities the policy addresses

- how the policy operates

- monitoring and evaluation of the policy

- accountability.

REFLECT:

Access the questions here.

Read through the questions and consider how they apply an intersectional lens to policy. What do you note? What questions arise for you?